- Home

- Alice Echols

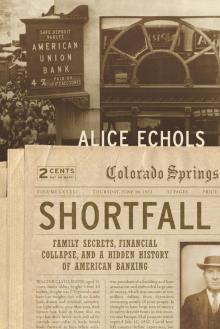

Shortfall

Shortfall Read online

ALSO BY ALICE ECHOLS

Hot Stuff: Disco and the Remaking of American Culture

Shaky Ground: The Sixties and Its Aftershocks

Scars of Sweet Paradise: The Life and Times of Janis Joplin

Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967–1975

© 2017 by Alice Echols

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2017 Distributed by Perseus Distribution

ISBN 978-1-62097-304-2 (e-book)

CIP data is available

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Composition by dix!

This book was set in Fairfield LH

Printed in the United States of America

24681097531

In memory of my mother

Shortfall, n.

A falling short; the amount by which a supply falls short, shortage, deficiency. Also, a decline; a shortcoming, a fault; a deficit, a gap; a loss.

—Oxford English Dictionary

Contents

Prologue: Captain Nothing

Part One

1:Advertisements for Himself

2:The Loan Man

3:Racketeers and Suckers

Part Two

4:Slipping Through Your Fingers

5:Sowing Grief

6:The Port of Missing Men

7:Orphans in the Storm

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Prologue

Captain Nothing

George Bailey. It’s a name that most Americans, or at least those of a certain age, recognize in a flash. With just a bit of prodding (“You know, Jimmy Stewart . . . It’s a Wonderful Life”), even those who have never watched the 1946 film in its entirety usually know whom it is you’re talking about. George Bailey is the small-town banker at the center of Frank Capra’s classic Hollywood movie. A man filled with dreams of a big and exciting life, he finds himself, when his father dies suddenly, stuck in his hometown, Bedford Falls. This untimely death shackles George to his father’s struggling building and loan association (B&L). Consigned to what he disparagingly calls this “business of nickels and dimes,” he tries to make the best of it, albeit grumpily at first. Kindhearted, altruistic, and willing to take on Henry Potter, the town’s evil banker, George is the sort of person most Americans have rarely, if ever, encountered in the world of financial services.

At the same time that George Bailey was doing his best to bring the American dream of homeownership to the working people of Bedford Falls, Walter Clyde Davis was operating a different kind of building and loan association in Colorado Springs, Colorado. George Bailey was a beloved figure, whereas Walter Davis aroused in others feelings of wariness, sometimes even dread. Yet Davis turned his building and loan into the biggest in central Colorado, with 3,600 depositors. His success enabled him to buy into a tony neighborhood, drive luxury cars, and finance summer-long European vacations for his family. And then there was Davis’s mistress, another telling difference between the real-life B&L man and his fictional counterpart.

Each man faced financial calamity during the Depression. But George Bailey selflessly handed out his own honeymoon money to forestall a bank run engineered by his nemesis, Henry F. Potter. By contrast, Walter Davis went on the lam before news of his association’s failure hit the papers. Back home in Colorado Springs, investigators discovered that the town’s “financial wizard” had left his business with a jaw-dropping $1.25 million shortfall. In today’s terms, that translates into nearly $22 million.1 When detectives arrested him that December, newspapers across America carried the news. Journalists knew the scandal would resonate with Americans who had come to view bankers as a species of gangster, or “bankster,” as they were sometimes called. Here was a man, argued one journalist, who had passed himself off as a captain of finance when he was a mere pretender. “A cabin boy, strutting the bridge in a captain’s uniform,” Walter Davis could now be seen for what he was: “Captain Nothing.”2

The building and loan industry, once a central part of our country’s financial fabric, is barely remembered today. What has lived on in our cultural memory is George Bailey, who has become a fixture in books about banking and finance, homeownership, and the Depression. As for Walter Davis, well, he’s pretty much gone missing from our history books.3 You certainly won’t find him in the standard histories of the “thrift industry,” the term used for the building and loan industry and the modern savings and loan business that succeeded it. According to these accounts, the vast majority of building and loans survived the Great Depression, and those that didn’t failed because of the collapse of the country’s real estate market, not because of any financial impropriety.4 Indeed, a number of scholars who have written about building and loans depict them as noble institutions—“banks with a soul”—and write as if the fictional Bailey Brothers Building and Loan Association was actually representative of the industry.5

In studio photographs, Walter Davis looks like someone with whom one would prefer not to tangle—very much the anti–George Bailey. (Author’s archive)

Midway through It’s a Wonderful Life, just as newlyweds George and Mary Bailey are heading off on their honeymoon, something goes terribly wrong—a bank run at Bailey Brothers Building and Loan. It’s 1932. The depositors are desperate but restrained, until they learn of Old Man Potter’s offer to pay fifty cents on the dollar for their B&L shares. George tries to win back his depositors by explaining the power dynamics behind Potter’s offer. However, the run only comes to an end after Mary hands over their honeymoon money to George, who selflessly distributes it to the crowd. (Image courtesy of Getty Images)

Yet among building and loan men of that period Walter Davis was hardly anomalous. Neither was his failure or the circumstances surrounding it. This is no small thing. During the Great Depression the industry’s cratering brought untold grief to millions of depositors. Despite this, the history of the American thrift industry during the interwar years remains hidden, buried in the bowels of state archives and local libraries.

My discovery of this forgotten financial history did not begin in the archive, however, but with an almost chance conversation some twenty years ago. I was home, visiting my parents, when the dinnertime banter one evening went too far. After my mother left the table, slamming shut her bedroom door for good measure, my father explained the roots of her cellophane-thin sensitivity. He spoke about her family, particularly her cad of a father. His was not a story with a Capra-like happy ending. Our conversation that night was my introduction to the man at the center of this book, a man whose name I did not yet know. Within our family everything about him—stories, photographs, and memorabilia—had been banished. Walter Clyde Davis, my grandfather, had been scrubbed as clean from my family as he was from the history books.

It’s embarrassing to admit, but until that evening it had never occurred to me that it was weird how little I knew about my mother’s past. Even though I grew up surrounded by her parents’ possessions, I

don’t recall ever inquiring about them or how they had come by all their swanky stuff. The room-sized Oriental rugs, the salmon-colored Art Deco chaise longue, the mahogany furniture—all of it was strikingly at odds with the midcentury blondness of my friends’ homes. And so it was with our pantry, crowded with variously sized Wedgewood plates, cups, saucers, and bowls, not to mention an array of delicate stemware for every conceivable kind of alcoholic drink. Some who have written about family secrets report a disjuncture between the accepted family narrative and their own perceptions, and others of being haunted by an unknown knowledge, what psychoanalysts have dubbed nescience.6 For example, in another book about real estate and lending that pivots on a family story, historian Beryl Satter writes that as a child she often felt as though she was “living in the aftermath of an explosion whose source was obscure.”7 Admittedly, the shattering events in her family’s story were not at a generational remove; still, how was it that I never registered as strange our home’s faded, antique opulence or our family’s conversational voids?

It would take several more years before a friend, another historian, persuaded me to start digging. Even then, it was she who did the first bit of spadework by searching for my grandfather in a bound volume of the New York Times index at the Santa Monica Public Library, then copying and mailing me the relevant articles. That was how I learned that Walter Davis was generally understood to have been an embezzler rather than the victim of the Depression that my father’s account had led me to believe.

Making sense of my grandfather then, in 1999, was much harder than it would have been even a few years earlier. By this juncture, my father was dead and my eighty-nine-year-old mother had an uncertain memory and was struggling with an unnamed neurological condition. Moreover, I had not yet broached the subject of the scandal to my mother, who was unaware I even knew about it. I could think of only one person—my father’s sister, a former nun—who might provide some useful information. What she had to offer was a vague memory of having been told that her sister-in-law’s father had owned large swaths of Wyoming. As for my mother’s relatives—or those who had lived through the scandal—they had all passed away, and nothing of their personal archive seemed to have remained. Then, a few years ago, a tiny collection of letters, diaries, and memorabilia belonging to my great-uncle, Roy Davis, a prominent local politician, found its way to the local Colorado Springs history museum. This tiny bundle represented a sliver of what was once his archive, which had been tossed into a dumpster after his death.

As it happened, I was just getting interested in investigating the scandal when my mother’s decline forced her to move into an assisted living facility. That meant putting our house on the market. We had moved to Chevy Chase Village from an adjacent Maryland suburb in the mid-1950s. Over the years, many of the houses in our neighborhood had been McMansioned. Ours, however, looked exactly as it did when we moved in. Little of what we accumulated in the subsequent forty-three years had been given away or junked. After a serious attempt at culling, my sister arranged for the remaining stuff in our basement to be hauled away. In the process, several mildewed trunks, whose contents our mother had described as worthless, became part of the junk heap. In the end, my sister unearthed several boxes of family memorabilia and I gathered up a handful of my mother’s designer clothes from the 1920s and a batch of family photographs, all of it from the sole surviving trunk—a beautiful, slightly worn Louis Vuitton that for decades sat closed, but likely unlocked, in one of the few dry spots in our basement.

The woman who bought our house, realizing that our mother was unable to clear it and that her daughters were unlikely to do so, and believing the house could do with a makeover, bought it “as is.” A year later, my sister and I were on the phone talking about the old neighborhood. She had recently spoken to neighbors who told her that the new owner was gutting the house. In passing, my sister mentioned the seventy or so boxes she had told the movers to leave behind in our attic. My sister had no idea I was weighing whether to research the scandal, so there was no reason she should have shared with me what was now a galvanizing detail.

Of course, the boxes would be in our attic, a space that always made me uneasy. It was where we stored our Christmas decorations, and when air-conditioning was finally installed, where some crucial bit of that system was located. Twice a year my father hauled a ladder in from the garage and made his way up it to retrieve and store again the unwieldy boxes that held our tree ornaments and Styrofoam Santa Claus. The combination of the wobbly ladder and my less than totally nimble father always made this a nerve-racking exercise. But I now wonder if some of my nervousness resulted from having picked up on my parents’ anxiety about what else was stored up there.

Whatever the source of that old anxiety, I was now fixated on those cardboard boxes. It turned out the renovation on our former house was proceeding so slowly that the contractor had yet to empty the attic. After I explained the outlines of the scandal to the new owner, she promised that once the boxes were downstairs she would open up each box and look inside to see which contained family papers and memorabilia. I would have preferred going through them myself, but I did not have the chutzpah to ask. A few weeks later we spoke on the phone and she reported that most of the boxes contained nothing worth keeping. A few of them, however, looked very promising indeed.

In those boxes were a seventy-page transcript of subpoenaed family telegrams, newspaper clippings, diaries, scrapbooks, correspondence, and photographs, including many of my self-regarding grandfather. Some of this material, including a bookstore clerk’s scribbled message to put aside a copy of Theodore Dreiser’s American Tragedy for Mrs. Walter Davis, seemed almost too spot-on. Often the most telling scraps had been tucked away inside diaries and books, one of them a copy of Poems That Have Helped Me, a gift that my grandfather sent to my grandmother while he was on the lam. All along an intimate archive of the scandal had been cached inside our house.8 My mother held on to it all, even though doing so risked the possibility that one of her daughters might eventually discover her family’s secret. Why hadn’t she thrown it all away when she moved east?

The material inside those boxes was indispensable, as was my grandfather’s two-hundred-page FBI file, acquired through a Freedom of Information Act request. Just as important were my mother’s contributions. The floodgates may not have opened when she first spoke about the scandal, but she became remarkably forthcoming. Several weeks into our talks she announced that she was granting me “permission” to write a book about the scandal. Sometimes, particularly after lengthy discussions that touched on parts of the story that had long since faded from her memory, I felt she regretted having given me her okay. Yet she continued talking to me about it, and over a period of two and a half years the scandal became a conversational staple. These were not structured interviews recorded on tape, but rather informal conversations. Her memory often failed her when it came to the details of the scandal, but parts of that experience remained indelibly with her. She often told me about coming downstairs for breakfast one morning and finding her father in a panic about the bad news in that day’s newspaper. “He saw it all coming,” she said. And then invariably she would add, “He blamed it all on Bubbles!”

My mother never could tell me who this Bubbles character was, but quite a lot of what she did tell me was borne out by my research. Was she really almost the victim of a kidnapping at the hands of depositors desperate to force her father’s return? Yes, that story made the front page of the local papers. Had her father’s grave been left unmarked out of fear that it might be desecrated or dug up in the hope that some part of his fortune had been buried with him? When my wife and I visited the cemetery where the Davis family is buried, we found that both of my grandparents’ graves were without headstones. Sometimes my mother’s memories were self-contradictory or at odds with what I discovered elsewhere. And I would not rule out the possibility that on occasion she tailored her story to fit what she believed were my expectati

ons. But her recollections of her feelings were fairly consistent. For a book such as this, which tries to impart a sense of the emotional textures of that time and place, and of the feelings of those most intimately connected to the scandal, her memories prove crucial.

Shortfall uses the building and loan scandal, particularly as it played out in Colorado Springs, in order to explore the relationship between capitalism, class, and conservatism in America. It asks why it is that when it comes to stories of financial failure, particularly stories of “bad capitalism,” forgetting seems so often to set in.

That I became less interested in what happened to the missing million and more intrigued by what the scandal might tell us about our country owes a lot both to our current economic and political landscape and to the nature of research itself. For me the shift began as it so often does for historians: squinting at a microfilmed copy of an old newspaper and finding myself drawn to a nearby article, one with no apparent relation to my topic. From these semi-distracted glances I would sometimes recognize a name, which occasionally led to unanticipated connections, be it to the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which successfully “kluxed” Colorado in the 1920s, or to the violent labor wars that preceded Klan activism there. As my research expanded into seemingly disparate corners of our country’s past, this book became not only my excavation of a buried financial history or a long-forgotten chapter in the history of a small Western city (or for that matter my own family’s history) but also a timely, on-the-ground history of twentieth-century American capitalism.

The first discovery I made as I researched the scandal was that the crash of my grandfather’s building and loan was not singular. By the summer of 1932 every single building and loan association in Colorado Springs had collapsed. With all four of its associations shuttered, the city was hit with an avalanche of failure.9 “What am I to do I can’t fathom,” wrote one penniless depositor. “I am nearly insane.”10 An unusually large number of Colorado Springs residents—between five thousand and six thousand in a city with ten thousand heads of household—were depositors in one of the four failed associations.11 The industry’s collapse hit with the force of a natural disaster, and residents frequently likened the financial meltdown to just such a catastrophe. However, what they experienced did not feel impersonal or random in the way that the loss from a tornado or an earthquake would. The Great Depression, which was key to the failure of the building and loan business, was a global phenomenon, but to those victimized by this industry’s collapse, there was nothing invisible or anonymous about it.12 That’s because the men running these associations were often trusted neighbors, fellow congregants at church, and sometimes even their children’s Sunday school teachers. They were not big-time, anonymous tycoons in faraway New York. Anxious about foreclosure, terrified of life with little or no financial cushion, association members absorbed what was happening to them as nothing less than a personal betrayal.

Shortfall

Shortfall